Moneuse route: the fall of a bandit, the birth of a legend - Quévy

Historic

in Quévy

-

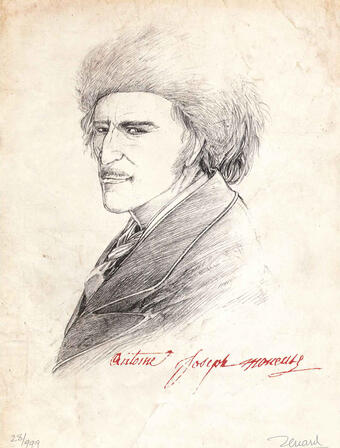

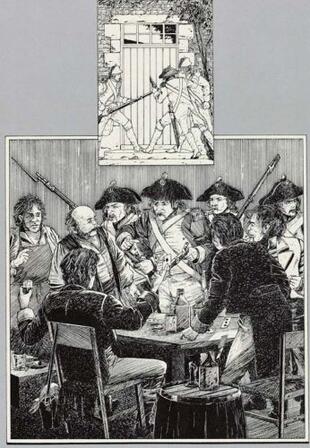

This route takes you in the footsteps of Antoine-Joseph Moneuse, the famous bandit and Captain of the Chauffeurs du Nord (heater uppers from the North of France and Belgium).

Here we will focus on this character’s downfall, from his arrest at Quévy-le-Petit through his sentences in Mons and Douai up to his execution on 18 June 1798.

But Moneuse’s story doesn’t stop at his death. It is only beginning thanks to popular legend. Here we will focus on the festival in Beria, a local folklore...This route takes you in the footsteps of Antoine-Joseph Moneuse, the famous bandit and Captain of the Chauffeurs du Nord (heater uppers from the North of France and Belgium).

Here we will focus on this character’s downfall, from his arrest at Quévy-le-Petit through his sentences in Mons and Douai up to his execution on 18 June 1798.

But Moneuse’s story doesn’t stop at his death. It is only beginning thanks to popular legend. Here we will focus on the festival in Beria, a local folklore largely inspired by Moneuse, which takes place every year in Quévy-le-Petit.

Have a good walk and watch out... Bandits are about.

The route follows that of the Beria one, created by not-for-profit organisation Petit Kévy with the support of Hauts-Pays natural park. Marker points and information signs are in place.

Route created and put together by Hauts-Pays natural park

Illustrations Claude Renard

- Points of interest

- 38 meters of difference in height

-

- Start altitude : 104 m

- End altitude : 104 m

- Maximum altitude : 109 m

- Minimum altitude : 90 m

- Total positive elevation : 38 m

- Total negative elevation : -38 m

- Max positive elevation : 13 m

- Min positive elevation : -9 m